Historically, manual processes have dominated the medication-use process and introduced the risk of human error. With the advent of bar coding, hospitals have been able to automate many pharmacy tasks, significantly increasing medication safety. While bar code technology implementation is now widespread, an ongoing reliance on laborious manual processes continues to present significant opportunities for medication errors to occur. A newer technology, radiofrequency identification (RFID), can supplement bar coding and other automation to improve safety and efficiency in the pharmacy.

What Is RFID Technology?

RFID is a novel technology that utilizes a small electronic device comprising a chip and an antenna. The chip carries a unique identifier for the object or medication to which it is adhered. Using RFID, items can be scanned within a few feet of a reader, as opposed to requiring direct contact, as is required with a bar code scanner. In addition, RFID readers can read hundreds of items at once.

For a conceptual example of the efficiencies gained with RFID technology, consider a supermarket checkout line. Each item must be individually bar code-scanned in order to be processed. Using RFID technology, all of the groceries could be placed on an RFID scanner and be read at once, significantly decreasing the time necessary to process items and tally prices. A University of Arkansas study found that scanning 10,000 items with bar code technology took 53 hours; when compared with RFID technology, the same 10,000 items were processed in just 2 hours.1

The current RFID market has an estimated value of over $10 billion annually.1 The majority of today’s RFID applications are found outside of health care, with large retailers demonstrating significant successes implementing this technology, particularly for supply chain integrity. In fact, large-box retailers have reported improvements in inventory tracking accuracy from 60% to greater than 95% after implementing RFID technology.2 RFID tags can also store more information than is currently possible with bar code technology. With increasing complexity in inventories—eg, multiple product sizes and colors, etc—RFID technology can track items to this level of specificity, which assists in maintaining an accurate inventory.1,2

These benefits have inspired other industries to incorporate RFID technology into workflows. RAIN RFID is a global alliance promoting the universal adoption of RFID technology (similar to other initiatives that exist for popular technologies, such as Bluetooth, WiFi, and near-field communication [NFC]). RAIN RFID utilizes cloud-based technology to connect RFID devices via wireless-based integration to facilitate universal adoption. RAIN may help apply the benefits of RFID more broadly across a variety of industries.1

While RFID technology can simplify labor-intensive workflows, it typically exists in combination with bar code technology, not in place of it. Both technologies have specific advantages and disadvantages that make them practical to incorporate in various management systems. While bar coding captures less data than RFID technology, RFID is more costly, so it may not be practical to transfer all bar coded items to an RFID solution.3

RFID Applications in Health Care

The benefits of RFID technology in non-health care fields can translate directly to health care, particularly in regard to efficiency, safety, and supply chain integrity. Real-time scanning positively impacts the pharmaceutical supply chain, ensures accurate inventory management, and increases operational efficiency and medication safety.

Supply Chain Management and Drug Shortages

Robust inventory management and smart ordering practices, combined with RFID technology, can help health systems significantly reduce waste. RFID technology can also assist in managing drugs on shortage as the technology pinpoints inventory location. In addition, the technology provides accurate, real-time data, allowing pharmacy to rapidly analyze and redeploy stock as necessary.2

Kit and Tray Management

RFID technology has gained rapid adoption in kit and tray assembly for emergency crash carts, anesthesia trays, and the like. Traditionally, kit and tray assembly has required a significant level of manual labor and oversight by pharmacy technicians and pharmacists, in order to verify that products are correct, lot numbers and expiration dates are recorded, and visual double-checks have occurred. Even those institutions using bar code scanning for tray assembly often are still required to manually enter expiration dates and lot numbers. The benefits RFID brings to crash cart assembly can be expanded to other areas that utilize kits, including rapid sequence intubation (RSI), open heart surgery, stroke, anesthesia, etc.4,5

Efficiency

Under RFID, most items must be manually tagged and loaded into the kit and tray system; however, the time necessary to complete this task is typically offset by the time saved through the assembly and checking of trays with the technology. Hundreds of items can be encoded with RFID tags at once, which improves efficiency. As RFID technology becomes more prevalent, manufacturers of medications that are commonly used in crash carts are beginning to introduce pre-tagged inventory with RFID capabilities that already contain a product’s NDC, expiration date, lot number, etc. Once items are tagged, assembled crash carts can be scanned and approved in less than 1 minute.6,7

Safety

RFID simplifies complex processes, eliminates manual assembly, and increases patient and employee safety by reducing the potential for human error.8

Conclusion

RFID technology is an underutilized resource that health-system pharmacies can leverage to gain efficiencies, enable smart inventory management practices, and improve medication safety. As this technology becomes more widespread and increasingly flexible in terms of cost and ease of implementation, RFID should be explored as an opportunity to improve pharmacy workflow and operations.

Nick Gazda, PharmD, BCPS, is a PGY2 health-system pharmacy administration resident at Moses H. Cone Memorial Hospital (MCMH) in Greensboro, North Carolina. He completed his BS at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and received his PharmD in 2016 from the UNC Eshelman School of Pharmacy. Nick is currently working toward his MS in pharmaceutical sciences with a concentration in health-system pharmacy administration from the UNC Eshelman School of Pharmacy. Starting in July 2018, he will step into the role of assistant director of specialty pharmacy at MCMH.

Kevin N. Hansen, PharmD, MS, BCPS, the assistant director of pharmacy at MCMH, provides oversight and leadership for pharmaceutical compounding and perioperative services pharmacy. He graduated from the Lake Erie College of Osteopathic Medicine with a Doctor of Pharmacy degree and received an MS in pharmaceutical sciences from the University of North Carolina Eshelman School of Pharmacy. Kevin’s professional interests include sterile compounding, quality assurance, and data analytics.

Kathleen E. Forbis, CPhT, AAS, is a advanced certified pharmacy technician at MCMH. She has an Associate’s Degree of Applied Science in pharmacy technology and is currently working on her BS in health care management. Kathleen’s areas of responsibility include sterile and non-sterile compounding, perioperative services, and code cart management.

Amber Santora, CPhT, is an advanced certified pharmacy technician at MCMH. Her areas of responsibility include perioperative services pharmacy and sterile compounding.

References

- Reaching New Frontiers with RFID [Thought Leadership]. Retail Info Systems Roadmap. September 2016. https://risnews.com/reaching-new-frontiers-rfid. Accessed March 8, 2018.

- Coustasse A, Tomblin S, Slack C. Impact of radio-frequency identification (RFID) technologies on the hospital supply chain: A literature review.Perspect Health Inf Manag. 2013 Fall;10(Fall):1d.

- Neuenschwander M. RFID vs bar coding: Should you wait for RFID before implementing bedside automation? Pharm Purch Prod. 2004;1(3).

- Enzor L. Use of RFID in the pharmacy and beyond. Pharm Purch Prod. 2016;13(6):20-21.

- Feemster AA, Shepardson A, Summerfield M. Product Spotlight: RFID Tray Replenishment from Kit Check. Pharm Purch Prod. 2012;9(11):40.

- Paaske S, Bauer A, Moser T, et al. The benefits and barriers to RFID technology in healthcare. Online J Nurs Infor. Summer 2017. 21(2). http://www.himss.org/library/benefits-and-barriers-rfid-technology-healthcare. Accessed March 14, 2018.

- 7 Reasons Why Hospitals Implement RAIN RFID Solutions. IMPINJ Inc. 2017. URL: https://www.impinj.com/media/3348/impinj_ebook_7reasonswhyhospitals-rain-rfid.pdf Accessed March 26, 2018.

- Ajami S, Rajabzadeh A. Radio Frequency Identification (RFID) technology and patient safety. J Res Med Sci. 2013;18(9):809-813.

- Thomas M, Sanborn MD, Couldry R. I.V. Admixture contamination rates: Traditional practice site versus a class 1000 cleanroom. Am J Health Sys Pharm. 2005;62(22):2386-2392.

SIDEBAR

Case Study: Implementing RFID at Cone Health

Cone Health, a six-hospital, community teaching health system with 1273 beds in Greensboro, North Carolina, recently implemented RFID technology for its adult and pediatric crash cart trays, emergency drug boxes, and anesthesia trays for procedural areas. Prior to installation, there was a documented 12% error rate for trays that were processed through Cone Health’s original, manual system. Since implementing RFID technology, there have been no reported errors. Robust planning and close collaboration with our RFID vendor during the implementation process were critical to the system’s success.

Pre-Implementation Steps

Prior to implementation, it is critical to analyze the current state of practice to identify all potential applications for RFID technology. This will provide a framework for choosing a vendor and for developing an implementation strategy. Recommended steps include the following:

Step 1: Take Stock

Make a list of every kit (eg, trays, boxes, packs) assembled or managed by pharmacy. Record the total number of medications and material items included in each kit as well as the dimensions of the kit.

Step 2: Collect Data

For each kit, indicate the replenishment schedule (eg, 24 hours, after each case, etc). After analyzing prior data, provide the average number of items replenished per cycle and an error rate for each. If data are not available, consider performing a small study over the course of 1-2 weeks to capture this information.

Step 3: Perform Time Studies

Perform time studies for replenishment of each kit type. Furthermore, indicate the time spent by each staff member (eg, pharmacy technician, pharmacist, etc).

Step 4: Analyze Data

Analyzing the data can help determine where the best opportunities for RFID implementation exist. Ideal kits to prioritize for implementation are those kits with high error rates and those requiring significant pharmacist and technician time.

Step 5: Assess Space

After determining the locations where RFID will be implemented, it is prudent to do a walk-through of the area and review the space. Each vendor offers various RFID scanner sizes; scanners can be placed on a cart, a countertop, or even mounted below the counter. Review the dimensions for the kits utilized in this space to ensure the appropriate RFID scanner is selected.

Step 6: Consider Workflow

Determine any workflow changes that will be required for successful RFID implementation at your institution, including inventory tagging, encoding, and quarantining stock for pharmacist approval.

Step 7: Identify Future Applications

Some vendors offer additional RFID technologies beyond those for standard kit replenishment, including RFID refrigerators and cabinets, and RFID anesthesia workstations. Assessing these additional technologies is an important consideration when choosing a vendor.

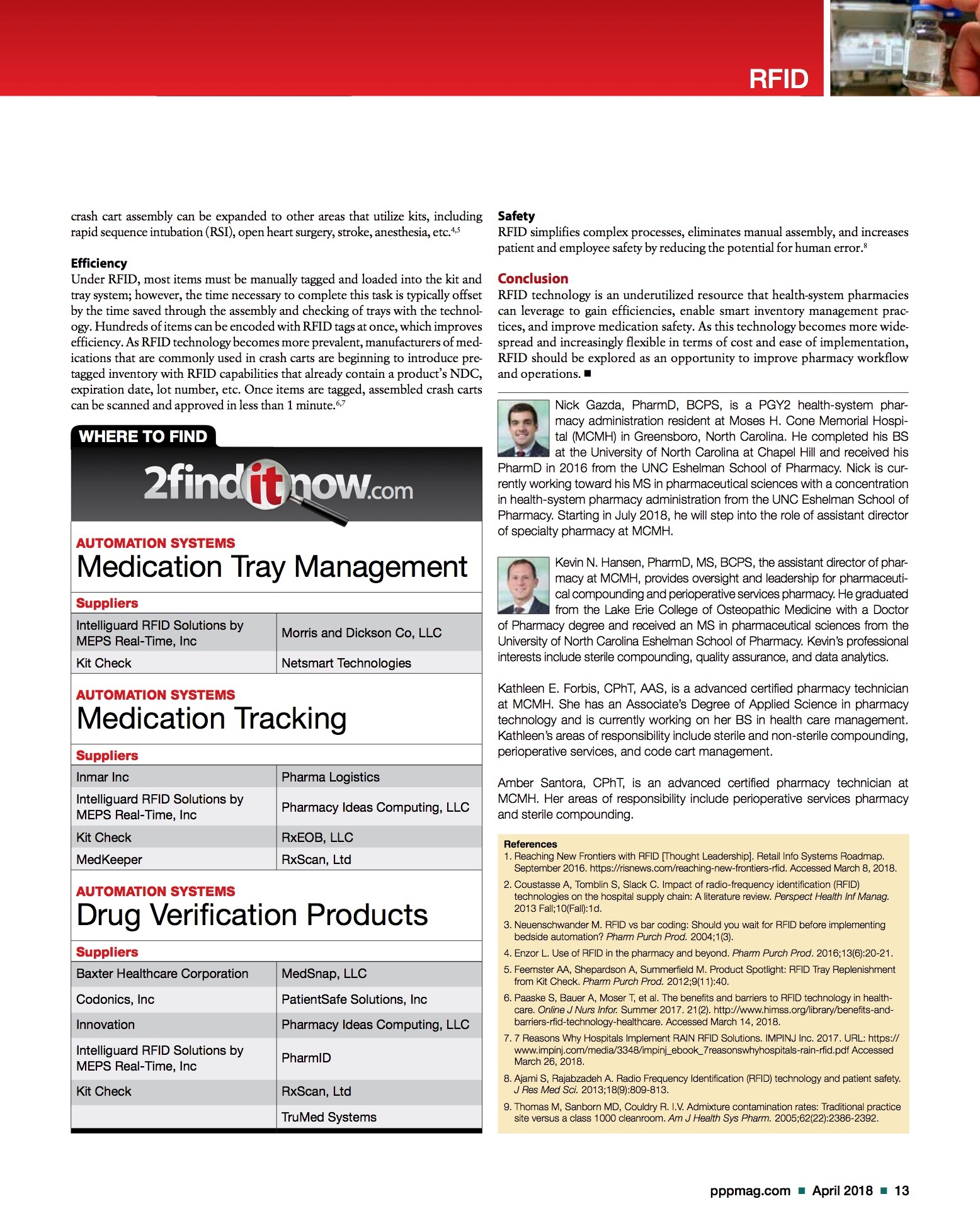

Step 8: Calculate ROI

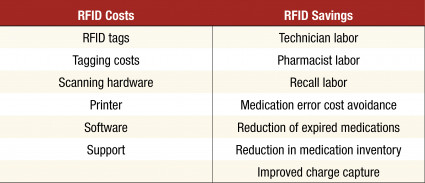

A 5-year ROI can be calculated using the following associated costs and savings that may be present:

Most vendors offer multiple cost models for their RFID technology. These include, but are not limited to:

- Tag-Only Model: All of the associated costs for the technology are included in the cost of each RFID tag. RFID tag costs are determined based on estimated volume of use, and the contract contains the minimum tag quantity purchase required to fulfill the agreement. RFID tag costs are higher in this model; however, the tag-only model avoids capital purchases or monthly fees.

- Capital Model: Equipment is purchased through the capital budget; thus, RFID tag costs are generally lower in this model. This may be disadvantageous if equipment becomes outdated or requires repair.

- Lease Model: A monthly fee is determined based on the combined number of workstations and the estimated volume of RFID tags required. The lease model may be advantageous because it allows scaling of increased use of the technology without penalty and avoids capital purchase.

Use the information collected from steps 1-9 to streamline vendor conversations and select the appropriate partner.

The Implementation Process

Working with the vendor, we developed an implementation plan focused on employee training, which was critically important to our success. We estimated that 3-4 weeks would be required to convert 90% of the trays and emergency drug boxes to RFID, considering the size and multi-site location of the health system and our average turnover rates. A support member from the vendor’s team would spend 1 week onsite to assist with implementation, training staff and establishing super-users, who would then train the other employees.We allocated one morning and one evening shift technician per day to train on the system and develop competencies as a super-user. These technicians were trained in tagging inventory, exchanging trays, creating new trays, and building tray and cart formularies. The IV room and OR pharmacists were rotated into training as well. This plan allowed us to best utilize the time our vendor spent onsite providing training support.During the training period, staff members and the vendor representative started prepping inventory and preparing trays to be converted. An estimated 50% of trays were converted in the first week of implementation. This achievement helped build competencies among employees and developed a strong foundation for ongoing training. Planning and building workflows prior to the vendor visit was crucial to maximizing the time that the vendor was on site.Prior to the implementation visit, vendor support via conference calls established that our proposed workflows would complement the RFID system. The workflow was designed to intentionally minimize pharmacist involvement. All medications stored in the kit and trays are tagged upon intake by a technician, and then quarantined for pharmacist approval.The pharmacist approval process is quick and efficient. Pharmacists are required to verify both quarantined stock as well as the final kit and tray. Technicians intake new inventory to tag, and the pharmacist then verifies and encodes all of the quarantined stock at one time. Once medications are encoded and approved, the medications are stored on RFID-labeled shelves adjacent to a picking station, for assembly by the technicians. Finally, pharmacists approve trays through the RFID system. Since the items in the tray are tagged, the system can read the tray’s contents, removing the manual process of checking products, expirations, and lot numbers. The pharmacist does a visual inspection and runs the tray through the RFID reader.Ongoing maintenance was necessary after the implementation week. A technician was scheduled to cover each shift, as available, for an additional 3 weeks, to provide support for tray turnover and conversion. These technicians also trained staff on the new software. Building in staffing support for the weeks after implementation was key to ensuring the full conversion of the kits and trays.

Training

With any new technology implementation, staff training and education are critical to ensure successful, streamlined operations. A multimodal approach to training is recommended, and should include:

- Train the Trainer: Develop super-user technicians and pharmacists who have increased knowledge of and access to the system. These staff members should receive early, dedicated training to build their knowledge base and comfort level with the technology. Super-users are then utilized to train additional staff.

- Hands-on Training Sessions: Inclusion of hands-on training sessions early during the implementation is important to ensure all staff have the opportunity to interact with the technology in a live setting and ask any questions they may have.

- Quick Reference Guides: Creating quick reference guides for various aspects of the workflow, and having these guides readily available for staff, has proven immensely helpful during the initial stages of training and for staff who interact with the technology less frequently. Cone Health’s Quick Reference Guide is available online at pppmag.com/RFIDQuickReferenceGuide.

- Workflow Breakdown: Include clear direction to staff outlining the new workflow and personnel responsible for each step. This information may include the specific time each task is to be performed.

- Assessing Knowledge: A comprehensive quiz based on the training documentation and workflow can be created to assess the staff’s understanding and to determine if additional training/educational sessions are required.

Cost

Cost is a significant consideration when implementing RFID technology in the pharmacy, as the RFID tags alone can add considerable expense to the department’s budget. Thus, we had to identify alternative methods to gain buy-in for RFID from hospital leadership. Since the technology significantly reduces technician and pharmacist time and associated labor costs, it was prudent to demonstrate the reallocation of the freed resources to other areas of the department without impacting FTEs. For those institutions that prioritize increasing staff efficiencies and developing lean processes, this can be leveraged to support the acquisition of RFID technology.Tagged Inventory

RFID technology may be deployed in areas where select inventory is used both in and outside of the kits. In this situation, it is important to consider having dedicated “tagged inventory” and “non-tagged inventory.” In these mixed-use areas, if items are only occasionally used outside of the kits—for example, a clinician requests an emergent medication for immediate use in the OR satellite pharmacy—this medication should be pulled from non-tagged inventory. This prevents wasting an RFID tag, which will not be scanned prior to use, and ensures that inventory remains accurate.

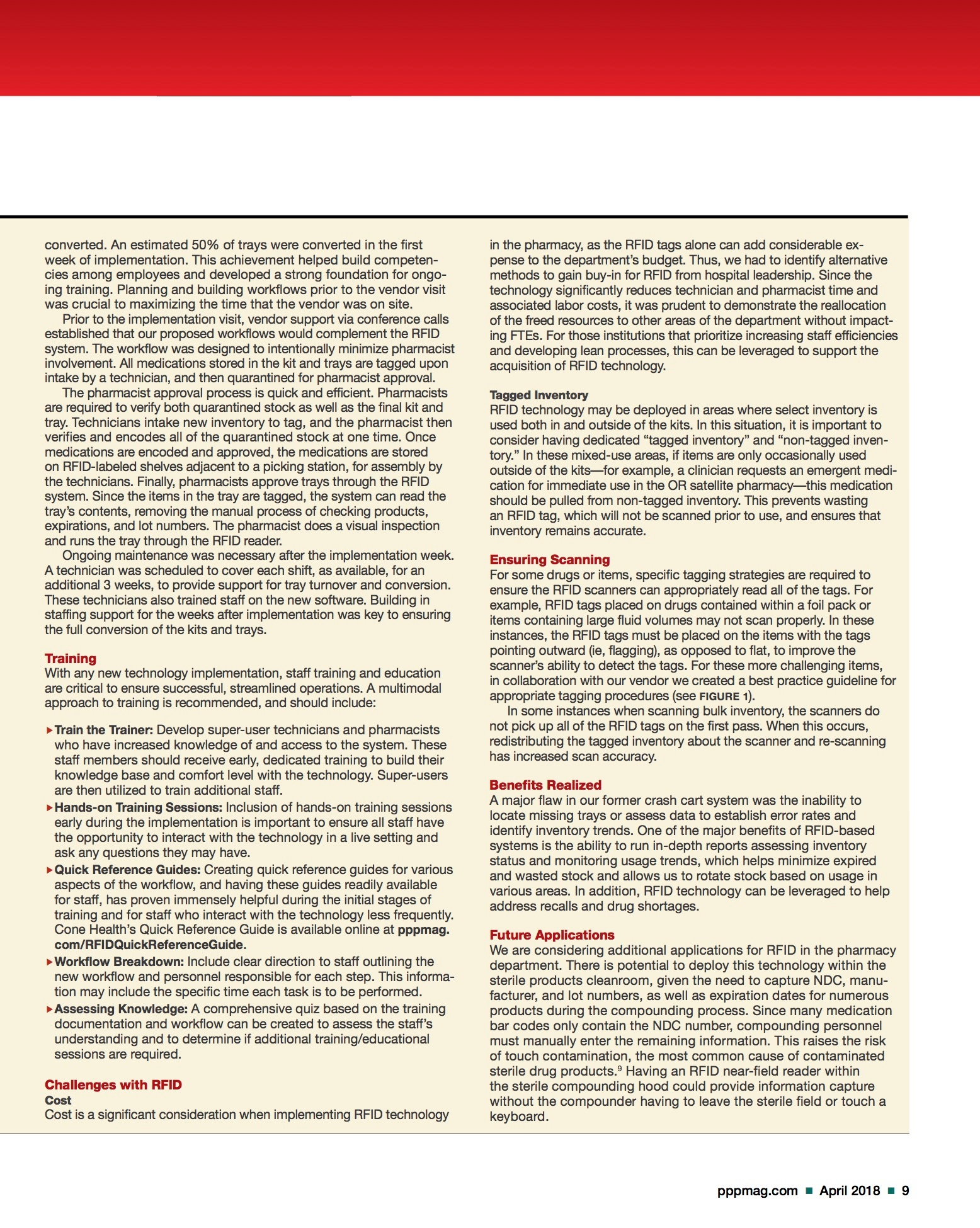

For some drugs or items, specific tagging strategies are required to ensure the RFID scanners can appropriately read all of the tags. For example, RFID tags placed on drugs contained within a foil pack or items containing large fluid volumes may not scan properly. In these instances, the RFID tags must be placed on the items with the tags pointing outward (ie, flagging), as opposed to flat, to improve the scanner’s ability to detect the tags. For these more challenging items, in collaboration with our vendor we created a best practice guideline for appropriate tagging procedures (see FIGURE 1).In some instances when scanning bulk inventory, the scanners do not pick up all of the RFID tags on the first pass. When this occurs, redistributing the tagged inventory about the scanner and re-scanning has increased scan accuracy.

A major flaw in our former crash cart system was the inability to locate missing trays or assess data to establish error rates and identify inventory trends. One of the major benefits of RFID-based systems is the ability to run in-depth reports assessing inventory status and monitoring usage trends, which helps minimize expired and wasted stock and allows us to rotate stock based on usage in various areas. In addition, RFID technology can be leveraged to help address recalls and drug shortages.

We are considering additional applications for RFID in the pharmacy department. There is potential to deploy this technology within the sterile products cleanroom, given the need to capture NDC, manufacturer, and lot numbers, as well as expiration dates for numerous products during the compounding process. Since many medication bar codes only contain the NDC number, compounding personnel must manually enter the remaining information. This raises the risk of touch contamination, the most common cause of contaminated sterile drug products.9Having an RFID near-field reader within the sterile compounding hood could provide information capture without the compounder having to leave the sterile field or touch a keyboard.